LEAVES FROM A NATURE NOTEBOOK: Something fishy...Eels and Conservation

A small plea on behalf of eels (and for a change in human thinking about nature.)

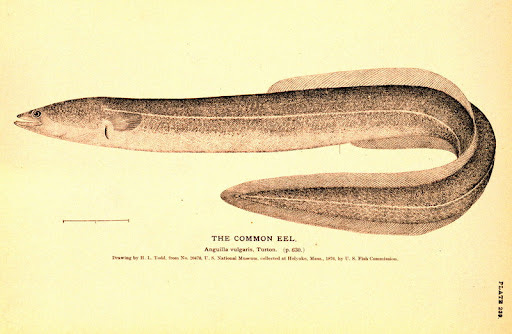

Slippery things, eels. The sliminess of their skin, according to one Victorian wag, makes them as difficult to grasp as a pig ‘which has been well soaped’. This physical elusiveness is, of course, a metaphor for the trickiness in pinning down the biology of the European eel, Anguilla anguilla. It is a fish that looks like a snake, and, like a snake, can travel overland. Stranger still, in its larval stage, it most resembles an amoeboid, being a flat transparent creature, shaped like a willow leaf, with a tiny head. Eels metamorphose, with a life cycle that for millennia baffled humans. Aristotle believed that eels emerged from ‘the entrails of the earth’, while Pliny the Elder, usually a fairly sober scientist, concluded that eels replicated by rubbing their bodies against rocks, and ‘from the shreds of skin thus detached come new ones’. It would be easy to scoff, except that the fantastic truth of eel reproduction was only fully proven in 1921, when the Danish scientist Johannes Schmidt, sailing the Sargasso Sea, at 26°N, 54°W, aboard the good ship Dana, finally discovered the species’ breeding grounds. Eels spawn in the Sargasso wastes of the Atlantic, then the larvae drift with the current to Europe where they grow into small transparent fish called ‘glass eels’. Glass eels grow into golden-yellow ‘elvers’ and, as a freshwater creature (another metamorphosis), snout their way up estuaries and rivers. After living for ten, twenty years, they then return to the ancestral spawning site on some dark night, and under some deus ex machina prompt mate in a giant, thrashing orgy, only to die and sink three miles down to the ocean floor. In this unlit graveyard, their million macabre corpses are finally scavenged by the lowest form of marine life, the holothurian, a creature that breathes through its anus. Schmidt may have discovered the breeding grounds of Anguilla anguilla, but to this day no one is sure how mature eels navigate the thousands of watery miles to their birthplace. Like everything about the eel, the reasons for its calamitous decline -95% globally since the 1970s- are mysterious, although shifts in the oceanic currents which bring the elvers to Europe and the pollution of waterways are causal contenders. And it is the eel’s bad luck to be enigmatic rather than charismatic. If it were feathery or furry, rather than serpenty and with a catholicity of appetite (encompassing cannibalism), would there not be a 38 Degrees petition launched on its behalf? There is a serious point here: the animals most promoted by conservation – I give you the wolf, the beaver and the hen harrier – are simply the animals humans find most engaging. Ranking animals in a value system is a human construction. Nature is indifferent, since, for nature, all animals have a role to play. The human tendency to promote certain species is actually a downright diversion from the needs of nature: the constantly proposed reintroduction of the wolf into Scotland, for example, will not create rich ecological change (‘trophic cascade’) by reducing the herds of overgrazing deer. It’s a Romantic dream. (You would need hundreds of wolf packs; it is not going to happen.) Meanwhile, the wolf gets lots of the oxygen of publicity…and the eel, none. But eels are a ‘keystone’ species, maintaining a balance in riverine ecology because they are a significant predator when adult (controlling populations of insects and other fish) and a significant prey when junior (a favourite snack for otter and herons, for example) . Eels are aquatic ecosystem managers. Once upon a time, the prolificity of eels in the estuarine Thames granted the city’s poor a cheap, nutritious, readily available food source. The Roman occupiers of Londinium ate eels, the Anglo-Saxons grilled eels lengthways (‘spatchcocking’), and in the nineteenth century jellied eels and stewed eels, sold first as street food and then from eel, pie and mash shops became the signature dish of the East End, as Cockney as the Bow Bells and Pearly Kings and Queens. The eel population in the Thames may have fallen by over 98 per cent this century. You would be hard pushed to find an eel in the Thames today to jelly, or pie. When we fail nature, we fail ourselves.

Great point about the charismatic species bias in modern conservation John. I think it is a great shame that the declines in the nondescript farmland birds e.g. Tree Sparrow and Corn Bunting don't get more air time. But perhaps the mote charismatic Turtle Dove and Cuckoo are functioning as "umbrella species" in conservation narratives.

A really fascinating piece, there is much I hadn't appreciated about this fascinating species. I do agree on the focus on the more "popular" species. We need to focus on getting all of nature back on track.